几何深度学习从对称性和不变性的角度处理广泛的ML问题,为神经网络架构的“动物园”提供了共同的蓝图。在我们关于几何深度学习起源的系列文章的最后一篇文章中,我们来看看图神经网络的前生。

图注:图片来自Shutterstock。

在“迈向几何深度学习”系列的最后一篇文章中,我们将讨论GNN的早期原型如何在20世纪60年代的化学领域出现。这篇文章基于M. M. Bronstein,J. Bruna,T. Cohen和P. Veličković 合著的《Geometric Deep Learning》(完稿后将由麻省理工学院出版社出版)书的介绍章节,以及我们开设的非洲机器智能硕士(AMMI)课程内容。请参阅我们讨论对称性的第一篇文章,以及关于神经网络早期历史、“AI冬天”的第二篇文章,以及研究第一个“几何”架构的第三篇文章。

如果对称性的历史与物理学紧密交织在一起,图神经网络作为几何深度学习的“典型代表”,它的历史植根于自然科学的另一个分支:化学。

化学在历史上一直是——现在仍然是——数据最密集的学科之一。十八世纪现代化学的出现导致了已知化合物的快速增长和对其组织的早期需求。这个角色最初由Chemisches Zentralblatt[1]和“化学词典”等期刊扮演,如Gmelins Handbuch der anorganischen Chemie(1817年首次出版的无机化合物的早期纲要[2])和Beilsteins Handbuch der organischen Chemie(有机化学的类似出版物) —— 所有这些都最初以德语出版,直到20世纪初才成为科学的主要语言。

在英语世界中,化学文摘服务(CAS)成立于1907年,并逐渐成为世界已发表化学信息的中央存储库[3]。然而,庞大的数据量(仅Beilstein就已经增长到500多卷,在其生命周期中增加了近50万页)很快就使打印和使用这种化学数据库变得不切实际。

图注:Gmelin的无机化学手册,这是两个世纪前首次出版的早期化学数据库。在数字计算机发展之前,化学家必须手动搜索这些数据库,这一过程可能需要数小时甚至数天。

大海捞针

自十九世纪中叶以来,化学家们已经建立了一种普遍理解的方式,通过结构式来指代化合物,表明化合物的原子,它们之间的键,甚至它们的3D几何形状。但是,这种结构并不容易检索。

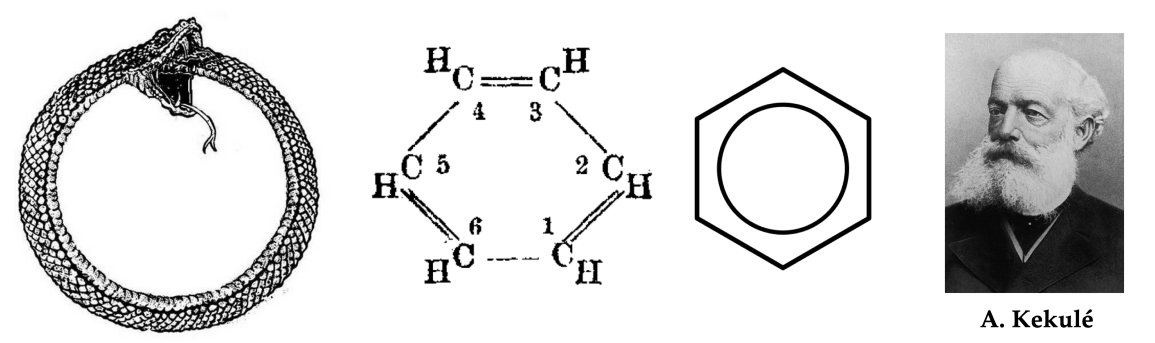

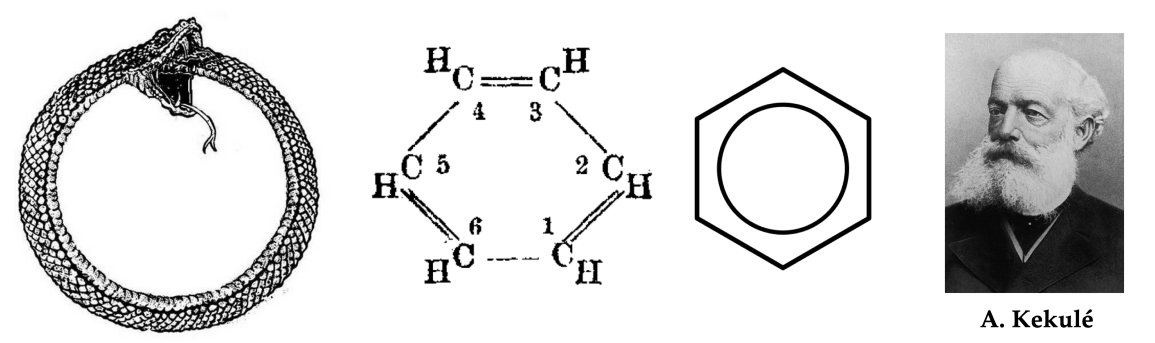

图注:苯(C₆H₆)的结构式由19世纪的德国化学家奥古斯特·凯库莱(August Kekulé)提出,并对苯环进行了现代描述。据说,凯库莱的灵感来自于一个梦中看到一条蛇咬自己的尾巴。

在20世纪上半叶,随着新发现的化合物及其商业用途的快速增长,组织,搜索和比较分子的问题变得至关重要:例如,当制药公司寻求为新药申请专利时,专利局必须验证以前是否注册过类似的化合物。

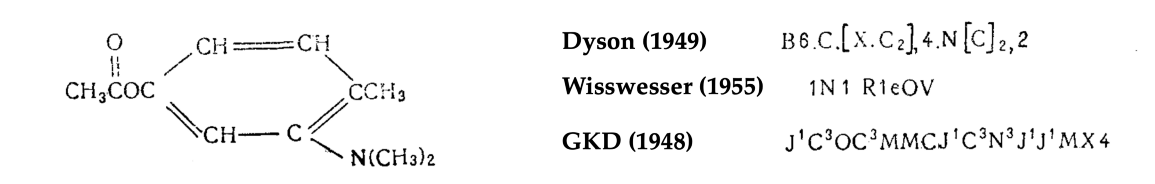

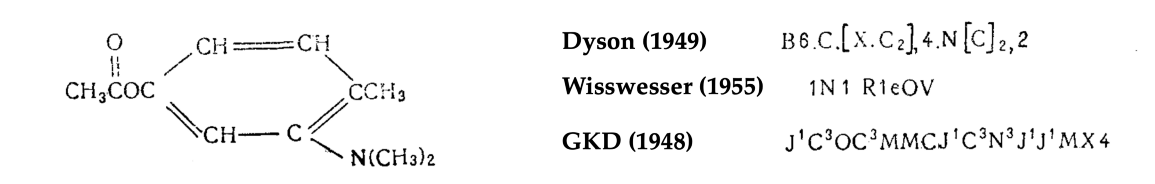

为了应对这一挑战,20世纪40年代,人们引入了几种用于索引分子的系统,为后来被称为化学信息学的新学科奠定了基础。比如有个这样的系统,由英国轮胎公司Dunlop开发,以作者Gordon,Kendall和Davison的名字命名为“GKD化学密码”[4],用于早期基于打孔卡的计算机[5]。从本质上讲,GKD密码是一种将分子结构解析为字符串的算法,使得人类或计算机可以更轻松地查找该字符串。

图注:化合物及其针对不同系统的密码示例。图片来自 [13]。

然而,GKD密码和其他相关方法[6]远非令人满意。在化合物中,相似的结构通常会导致相似的性质。化学家通过直觉训练来发现这些类比,并在比较化合物时寻找它们。例如,苯环与气味性质的联系是19世纪“芳香族化合物”化学类别命名的原因。

另一方面,当分子表示为字符串时(例如在GKD密码中),单个化学结构的成分可以被映射到密码的不同位置。结果,两个含有相似子结构(因此可能相似性质)的分子可能以非常不同的方式编码。

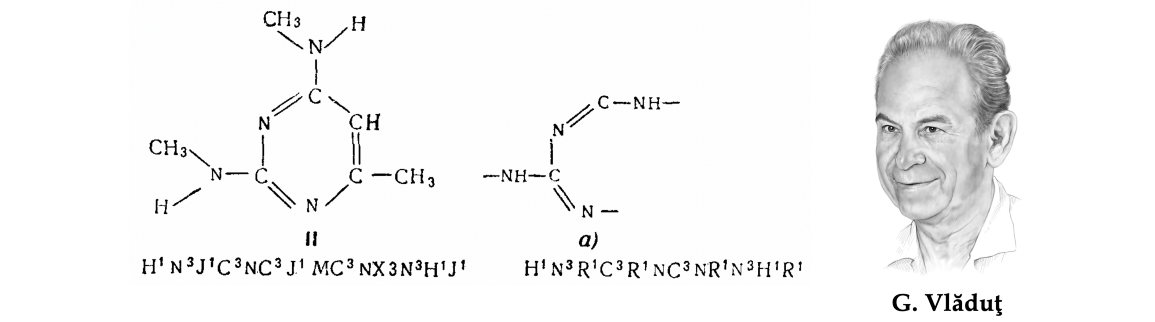

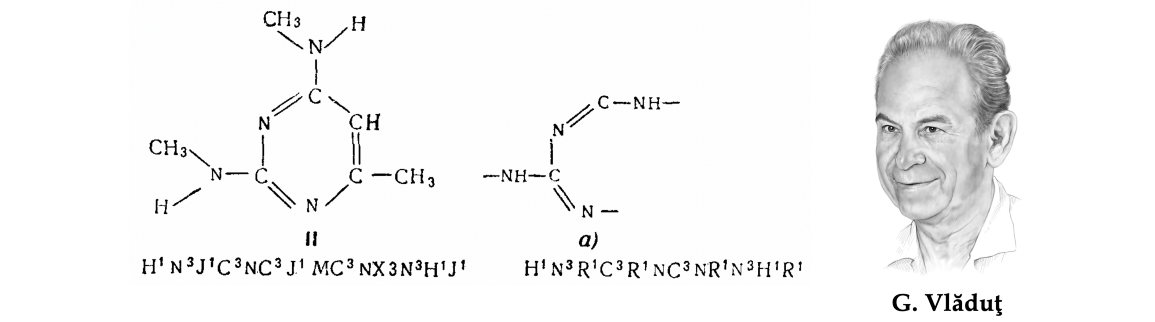

图注:乔治·弗拉杜特(George Vlăduţ)1959年论文[13]中的一个数字显示了一种化学分子及其碎片以及相应的GKD密码。请注意,这种编码系统破坏了分子中连接原子的空间局部性,使得片段密码无法通过完整分子的简单子字符串匹配找到。早期化学表示方法的这个缺点是用图形来搜索分子结构的动机之一。

这种认识鼓励了“拓扑密码”的发展,它试图捕获分子的结构。这方面的第一批工作是在陶氏化学公司[7]和美国专利局[8]完成的,它们都是化学数据库的重度用户。其中最著名的描述符之一,被称为“摩根指纹”[9],由Harry Morgan在化学文摘服务社[10]开发,并一直使用到今天。

化学与图论相遇

在开发早期搜索化学数据库的“结构”方法方面发挥关键作用的人物是罗马尼亚出生的苏联研究员George Vlăduţ[11]。作为一名训练有素的化学家(他于1952年在莫斯科门捷列夫研究所攻读有机化学博士学位),他在大一时经历了一次与庞大的Beilstein手册的“痛苦”相遇[12],使得他的研究兴趣转向了化学信息学[13]——他余生为之奋斗的领域。

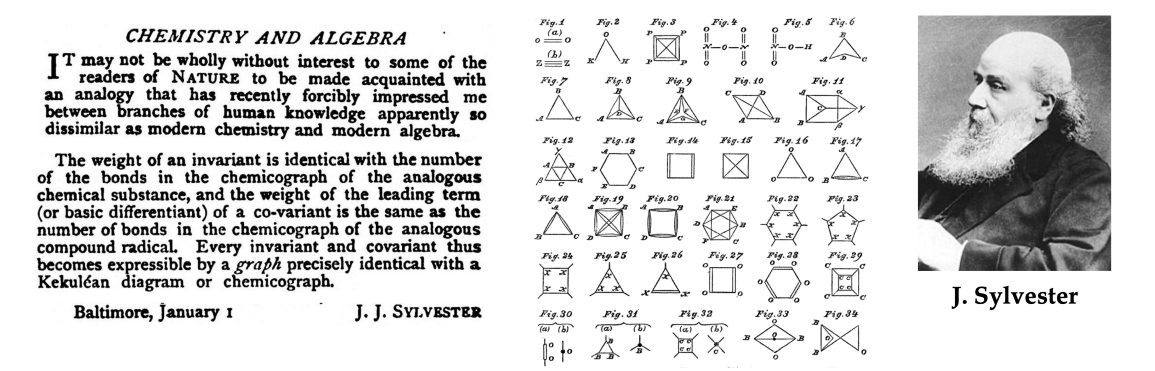

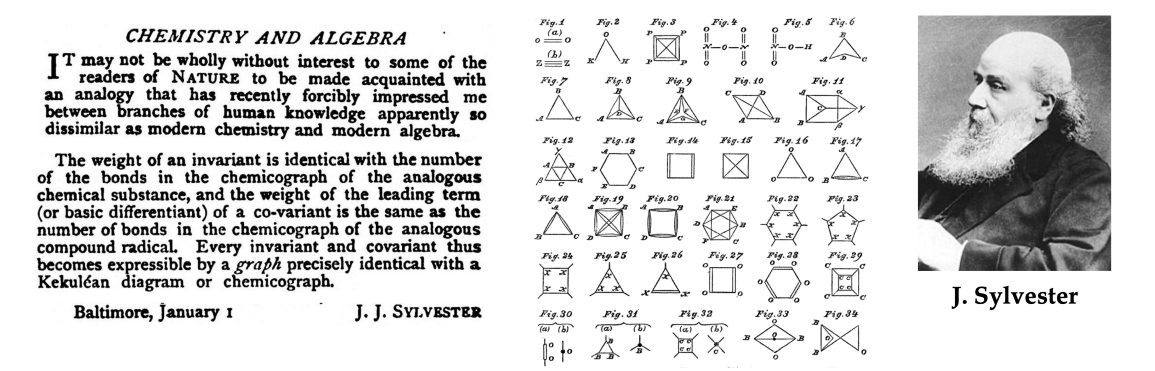

Vlăduţ被认为是使用图论来模拟化合物结构和反应的先驱之一。从某种意义上说,这并不奇怪:图论在历史上一直与化学联系在一起,甚至“图”这个词(指一组节点和边缘,而不是函数的图)也是由数学家James Sylvester在1878年引入的,作为化学分子的数学抽象[14]。

图注:术语“图”(在图论中使用的意义上)最初是由James Sylvester在1878年的《自然》杂志笔记中作为分子模型引入的[14]。

特别是,Vlăduţ主张将分子结构比较公式化为图同构问题;他最著名的工作是将化学反应分类为反应物和产物分子的部分同构(最大共性子图)[15]。

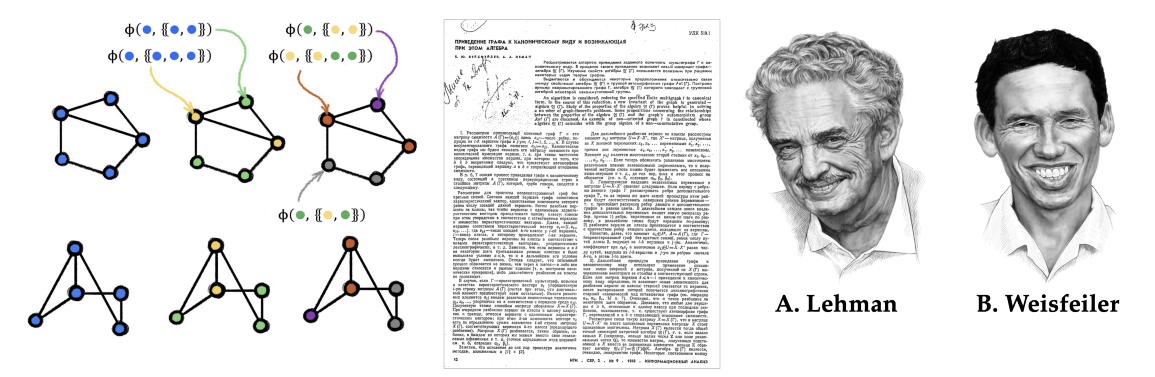

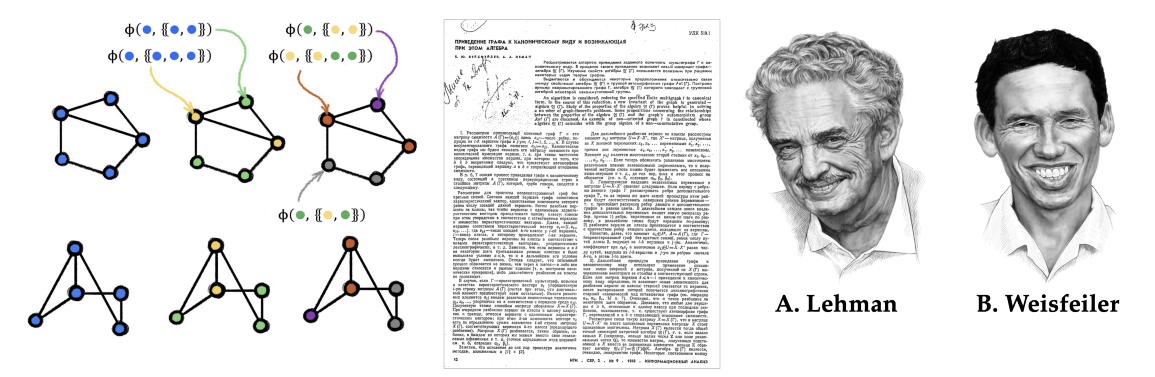

Vlăduţ的工作启发了一对年轻的研究人员[16],Boris Weisfeiler(代数几何学家)和Andrey Lehman[17](自称为“程序员”[18])。在一篇经典的联合论文[19]中,两人引入了一种迭代算法来测试一对图是否同构(即,这些图具有相同的结构,直到节点重新排序),这被称为Weisfeiler-Lehman(WL)测试[20]。虽然两人从上学时代就认识了,但他们在出版后不久便分道扬镳、在各自的领域发展了[21]。

Weisfeiler和Lehman最初的猜想,即他们的算法解决了图同构问题(并且在多项式时间内做到了)是不正确的:虽然Lehman在最多有九个节点的图的计算上证明了它[22],但一年后发现了一个更大的反例[23](事实上,一个被称为收缩手图的、在WL测试中失败的强正则图,甚至更早已为人所知[24])。

图注:1968年Andrei Lehman和Boris Weisfeiler引入的图同构测试。

Weisfeiler和Lehman的论文已经成为理解图同构的基础。从历史的角度来看,人们应该记住,在1960年代,复杂性理论仍处于萌芽阶段,算法图论只是迈出了第一步。正如雷曼在1990年代后期回忆的那样,

“在60年代,人们可以在几天内重新发现图同构理论中的所有事实、思想和技术。我怀疑,“理论”这个词是否适用;一切都处于如此基本的水平。“——安德烈·雷曼,1999年

他们的结果激发了许多后续工作,包括高维图同构测试[25]。在图神经网络的背景下,图同构测试与消息传递的等价性的证明[26-27],Weisfeiler和Lehman最近成为家喻户晓的名字。

早期图神经网络

尽管几十年来,化学家们一直在使用类似GNN的算法,但很可能他们在分子表示方面的工作在机器学习社区中仍然不为人知[28]。我们发现很难精确地确定图神经网络的概念何时开始出现:部分原因是大多数早期工作都没有将图作为“一等公民”,部分原因是图神经网络直到2010年代后期才变得实用,部分原因是该领域是基于几个相邻研究领域的融合而出现的。

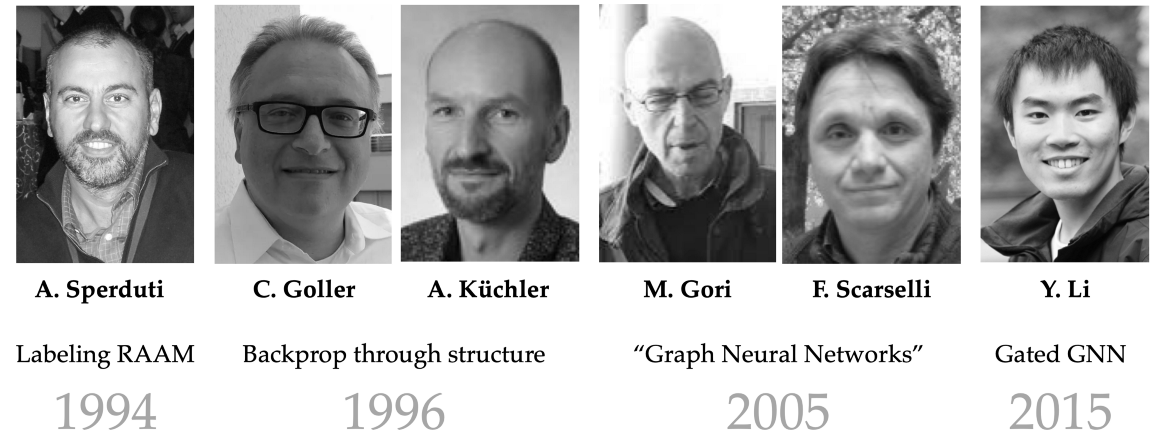

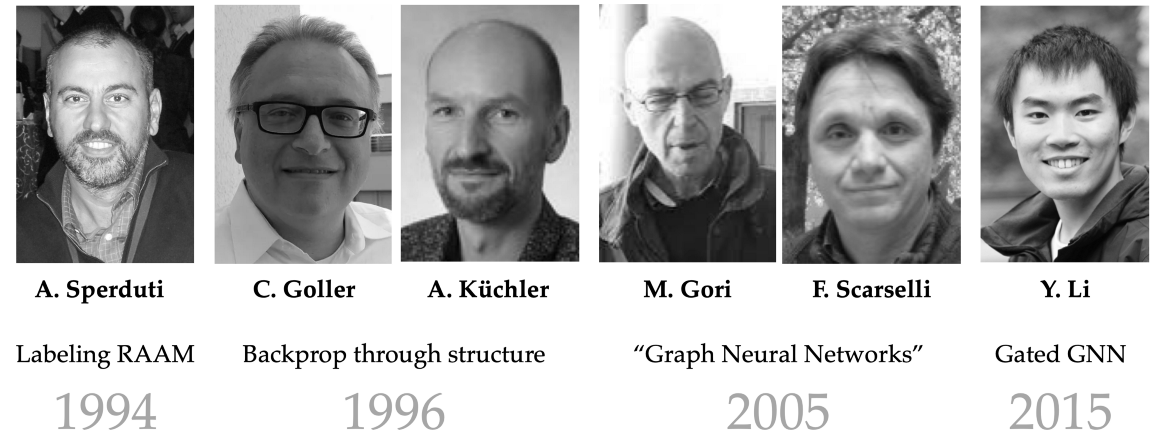

图神经网络的早期形式至少可以追溯到20世纪90年代,其中的例子包括Alessandro Sperduti的“Labeling RAAM”[29],Christoph Goller和Andreas Küchler的“通过结构反向传播”[30],以及数据结构的自适应处理[31-32]。虽然这些作品主要关注在“结构”(通常是树或有向无环图)上运行,但其架构中保留的许多不变性让人想起今天更常用的GNN。

图注:迈向图神经网络:20世纪90年代的早期工作侧重于学习泛型结构,如树或有向无环图。术语“图神经网络”是在Marco Gori和Franco Scarselli的经典论文中引入的。

第一次正确处理通用图结构(以及术语“图神经网络”的创造)发生在21世纪之交之后。由Marco Gori[33]和Franco Scarselli[34]领导的锡耶纳大学团队提出了第一个“GNN”。他们依赖于递归机制,需要神经网络参数来指定收缩映射,从而通过搜索固定点来计算节点表示 ——这本身就需要一种特殊形式的反向传播,并且根本不依赖于节点特征。上述所有问题都由Yujia Li的 Gated GNN (GGNN)模型[35]进行了纠正,该模型带来了现代RNN的许多好处,例如门控机制[36]和随时间的反向传播。

Alessio Micheli大约在同一时间提出的图神经网络(NN4G)[37]使用前馈而不是循环架构,实际上更类似于现代GNN。

图注:作者与GNN先驱Marco Gori和Alessandro Sperduti在WCCI 2022。

另一类重要的图神经网络,通常被称为“谱”,已经从Joan Bruna和合著者的工作中出现[38],使用图傅里叶变换的概念。这种结构的根源在于信号处理和计算谐波分析社区,其中非欧几里得信号的处理在2000年代末和2010年代初变得突出[39]。

来自Pierre Vandergheynst [40]和José Moura[41]小组的一系列重要论文推广了“图信号处理”(GSP)的概念以及基于图邻接和拉普拉斯矩阵的特征向量的傅里叶变换的推广。依赖于Michaël Defferrard[42]和Thomas Kipf和Max Welling[43]的频谱滤波器的图卷积神经网络,是该领域引用最多的网络之一。

回到起源

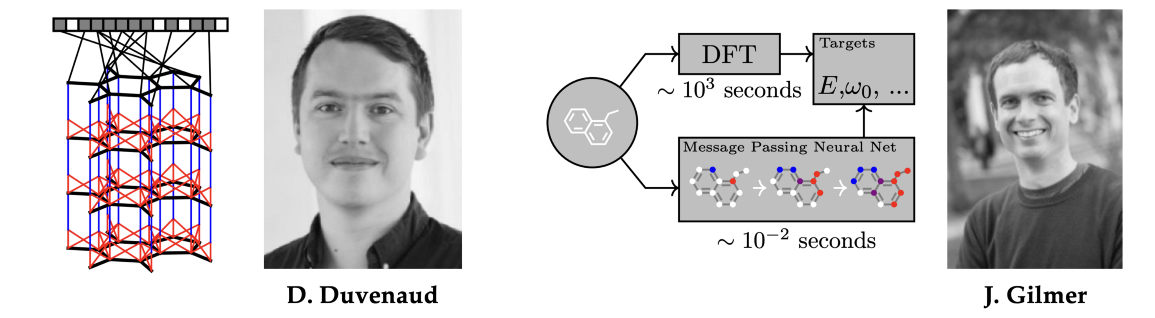

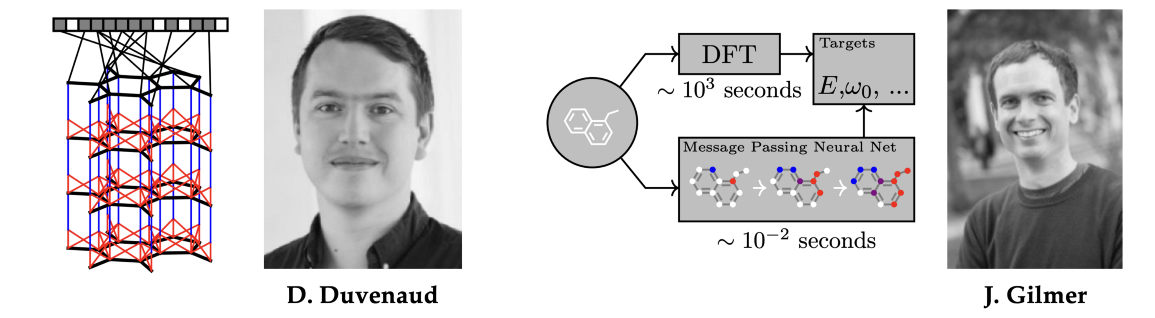

经过一个有点讽刺意味的命运转折,现代GNNs胜利地重新引入化学领域,它们起源于这个领域:由David Duvenaud[44]作为手工制作的摩根分子指纹的替代品,以及Justin Gilmer[45]以类似于Weisfeiler-Lehman测试的消息传递神经网络形式[26-27]。五十年后,这个圈子终于形成了闭环。

图注:图神经网络的现代版本随着David Duvenaud和Justin Gilmer的作品胜利地回归化学。

图神经网络现在是化学领域的标准工具,并且已经在药物发现和设计管道中使用。2020年基于GNN的新型抗生素化合物发现[46]获得了显着的赞誉。DeepMind的AlphaFold 2 [47]使用等变注意力(一种解释原子坐标连续对称性的GNN形式)来解决结构生物学的“圣杯”——蛋白质折叠的问题。

1999年,Andrey Lehman写信给一位数学家同事说,他“很高兴得知'魏斯费勒-莱曼'是众所周知的,并且仍然引起了人们的兴趣“,他没有活着看到基于他五十年前的工作的GNN的兴起。George Vlăduţ没有看到他思想的实现,其中许多思想在他有生之年一直留在纸上。但我们相信,他们会为开创了这个令人兴奋的新领域的源头而感到自豪。

参考文献:

[1] Originally Pharmaceutisches Central-Blatt, it was the oldest German chemical abstracts journal published between 1830 and 1969.

[2] Named after Leopold Gmelin who published the first version in 1817, the Gmelins Handbuch last print edition appeared in the 1990s. The database currently contains 1.5 million compounds and 1.3 million different reactions discovered between 1772 and 1995.

[3] In 1906, the American Chemical Society authorised the publication of Chemical Abstracts, charging it with the mission of abstracting the world’s literature of chemistry and assigning an initial budget of fifteen thousand dollars. The first publication appeared in 1907 under the stewardship of William Noyes. Over a century since its establishment, the CAS contains nearly 200 million organic and inorganic substances disclosed in publications since the early 1800s.

[4] M. Gordon, C. E. Kendall, and W. H. T. Davison, Chemical Ciphering: a Universal Code as an Aid to Chemical Systematics (1948), The Royal Institute of Chemistry.

[5] A special purpose computer (“Electronic Structural Correlator”), to be used in conjunction with a punch card sorter, was proposed by the Gordon-Kendall-Davison group in connection with their system of chemical ciphering, but never built.

[6] There were several contemporaneous systems that competed with each other, see W. J. Wisswesser, 107 Years of line-formula notations (1968), J. Chemical Documentation 8(3):146–150.

[7] A. Opler and T. R. Norton, A Manual for programming computers for use with a mechanized system for searching organic compounds (1956), Dow Chemical Company.

[8] L. C. Ray and R. A. Kirsch, Finding chemical records by digital computers (1957), Science 126(3278):814–819.

[9] H. L. Morgan. The generation of a unique machine description for chemical structures — a technique developed at Chemical Abstracts Service (1965), J. Chemical Documentation 5(2):107–113.

[10] Not much biographical information is available about Harry Morgan. According to an obituary, after publishing his famous molecular fingerprints paper, he moved to a managerial position at IBM, where he stayed until retirement in 1993. He died in 2007.

[11] In Russian publications, Vlăduţ’s name appeared as Георгий Эмильевич Влэдуц, transliterated as Vleduts or Vladutz. We stick here to the original Romanian spelling.

[12] According to Vladimir Uspensky, Vlăduţ told the anecdote of his encounter with Beilstein in the first lecture of his undergraduate course on organic chemistry during his Patterson-Crane Award acceptance speech at the American Chemical Society. See В. А. Успенский, Труды по нематематике (2002).

[13] Г. Э. Влэдуц, В. В. Налимов, Н. И. Стяжкин, Научная и техническая информация как одна из задач кибернетики (1959), Успехи физических наук 69:1.

[14] J. J. Sylvester, Chemistry and algebra (1878), Nature 17:284.

[15] G. E. Vleduts, Concerning one system of classification and codification of organic reactions (1963), Information Storage and Retrieval 1:117–146.

[16] We were unable to find solid proof of whether or how Weisfeiler and Lehman interacted with Vlăduţ, as most of the people who had known both are now dead. The strongest evidence is a comment in their classical paper [19] acknowledging Vlăduţ for “formulating the problem” (“авторы выражают благодарность В. Э. Влэдуцу за постановку задачи”). It is also certain that Weisfeiler and Lehman were aware of the methods developed in the chemical community, in particular the method of Morgan [9], whom they cited in their paper as a “similar procedure.”

[17] Andrey Lehman’s surname is often also spelled Leman, a variant that he preferred himself, stating in an email that the former spelling arose from a book by the German publisher Springer who believed “that every Leman is a hidden Lehman”. Since Lehman’s family had Teutonic origins by his own admission, we stick to the German spelling.

[18] Lehman unsuccessfully attempted to defend a thesis based on his work on graph isomorphism in 1971, which was rejected due to the personal enmity of the head of the dissertation committee with a verdict “it is not mathematics.” To this, Lehman bitterly responded: “I am not a mathematician, I am a programmer.” He eventually defended another dissertation in 1973, on topics in databases.

[19] Б. Вейсфейлер, А. Леман, Приведение графа к каноническому виду и возникающая при этом алгебра (1968), Научно-техн. информ. Сб. ВИНИТИ 2(9):12–16 (see English translation).

[20] There are in fact multiple versions of the Weisfeiler-Lehman test. The original paper [19] described what is now called the “2-WL test,” which is however equivalent to 1-WL or node colour refinement algorithm. See our previous blog post on the Weisfeiler-Lehman tests.

[21] Since little biographical information is available in English on our heroes of yesteryear, we will use this note to outline the rest of their careers. All the three ended up in the United States. George Vlăduţ applied for emigration in 1974, which was a shock to his bosses and resulted in his demotion from the head of laboratory post (emigration was considered a “mortal sin” in the USSR — to people from the West, it is now hard to imagine what an epic effort it used to be for Soviet citizens). Vlăduţ left his family behind and worked at the Institute for Scientific Information in Philadelphia until his death in 1990. Being of Jewish origin, Boris Weisfeiler decided to emigrate in 1975 due to growing official antesemitism in the USSR — the last drop was the refusal to publish a monograph on which he had worked extensively as too many authors had “non-Russian last names.” He became a professor at Pennsylvania State University working on algebraic geometry after a short period of stay at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton. An avid mountaineer, he disappeared during a hike in Chile in 1985 (see the account of Weisfeiler’s nephew). Andrey Lehman left the USSR in 1990 and subsequently worked as programmer in multiple American startups. He died in 2012 (see Sergey Ivanov’s post).

[22] А. Леман, Об автоморфизмах некоторых классов графов (1970), Автоматика и телемеханика 2:75–82.

[23] G. M. Adelson-Velski et al., An example of a graph which has no transitive group of automorphisms (1969), Dokl. Akad. Nauk 185:975–976.

[24] S. S. Shrikhande, The uniqueness of the L₂ association scheme (1959), Annals of Mathematical Statistics 30:781–798.

[25] L. Babai, Graph isomorphism in quasipolynomial time (2015), arXiv:1512.03547.

[26] K. Xu et al., How powerful are graph neural networks? (2019), ICLR.

[27] C. Morris et al., Weisfeiler and Leman go neural: Higher-order graph neural networks (2019), AAAI.

[28] In the chemical community, multiple works proposed GNN-like models including D. B. Kireev, Chemnet: a novel neural network based method for graph/property mapping (1995), J. Chemical Information and Computer Sciences 35(2):175–180; I. I. Baskin, V. A. Palyulin, and N. S. Zefirov. A neural device for searching direct correlations between structures and properties of chemical compounds (1997), J. Chemical Information and Computer Sciences 37(4): 715–721; and C. Merkwirth and T. Lengauer. Automatic generation of complementary descriptors with molecular graph networks (2005), J. Chemical Information and Modeling, 45(5):1159–1168.

[29] A. Sperduti, Encoding labeled graphs by labeling RAAM (1994), NIPS.

[30] C. Goller and A. Kuchler, Learning task-dependent distributed representations by backpropagation through structure (1996), ICNN.

[31] A. Sperduti and A. Starita. Supervised neural networks for the classification of structures (1997), IEEE Trans. Neural Networks 8(3):714–735.

[32] P. Frasconi, M. Gori, and A. Sperduti, A general framework for adaptive processing of data structures (1998), IEEE Trans. Neural Networks 9(5):768–786.

[33] M. Gori, G. Monfardini, and F. Scarselli, A new model for learning in graph domains (2005), IJCNN.

[34] F. Scarselli et al., The graph neural network model (2008), IEEE Trans. Neural Networks 20(1):61–80.

[35] Y. Li et al., Gated graph sequence neural networks (2016) ICLR.

[36] K. Cho et al., Learning phrase representations using RNN encoder-decoder for statistical machine translation (2014), arXiv:1406.1078.

[37] A. Micheli, Neural network for graphs: A contextual constructive approach (2009), IEEE Trans. Neural Networks 20(3):498–511.

[38] J. Bruna et al., Spectral networks and locally connected networks on graphs (2014), ICLR.

[39] It is worth noting that in the field of computer graphics and geometry processing, non-Euclidean harmonic analysis predates Graph Signal Processing by at least a decade. We can trace spectral filters on manifolds and meshes to the works of G. Taubin, T. Zhang, and G. Golub, Optimal surface smoothing as filter design (1996), ECCV. These methods became mainstream in the 2000s following the influential papers of Z. Karni and C. Gotsman, Spectral compression of mesh geometry (2000), Computer Graphics and Interactive Techniques, and B. Lévy, Laplace-Beltrami eigenfunctions towards an algorithm that “understands” geometry (2006), Shape Modeling and Applications.

[40] D. I. Shuman et al., The emerging field of signal processing on graphs: Extending high-dimensional data analysis to networks and other irregular domains (2013), IEEE Signal Processing Magazine 30(3):83–98.

[41] A. Sandryhaila and J. M. F. Moura, Discrete signal processing on graphs (2013), IEEE Trans. Signal Processing 61(7):1644–1656.

[42] M. Defferrard, X. Bresson, and P. Vandergheynst, Convolutional neural networks on graphs with fast localized spectral filtering (2016), NIPS.

[43] T. Kipf and M. Welling, Semi-supervised classification with graph convolutional networks (2017), ICLR.

[44] D. K. Duvenaud et al., Convolutional networks on graphs for learning molecular fingerprints (2015), NIPS.

[45] J. Gilmer et al., Neural message passing for quantum chemistry (2017), ICML.

[46] J. M. Stokes et al., A deep learning approach to antibiotic discovery (2020) Cell 180(4):688–702.

[47] J. Jumper et al., Highly accurate protein structure prediction with AlphaFold, Nature 596:583–589, 2021.

The portraits were hand-drawn by Ihor Gorskiy. We are grateful to Mikhail Klin for his historical remarks and to Serge Vlăduţ for providing the photo of his father. Detailed lecture materials on Geometric Deep Learning are available on the project webpage. See Michael’s other posts in Towards Data Science, subscribe to his posts, get Medium membership, or follow Michael, Joan, Taco, and Petar on Twitter.

内容中包含的图片若涉及版权问题,请及时与我们联系删除

评论

沙发等你来抢